- PEDS·DOC·TALK

- Posts

- Same Nutrition Advice with Different Optics: The New Dietary Guidelines

Same Nutrition Advice with Different Optics: The New Dietary Guidelines

Why the messaging feels more confusing than the guidance itself

Last week, the 2025–2030 Dietary Guidelines for Americans were released, and they quickly sparked a lot of conversation.

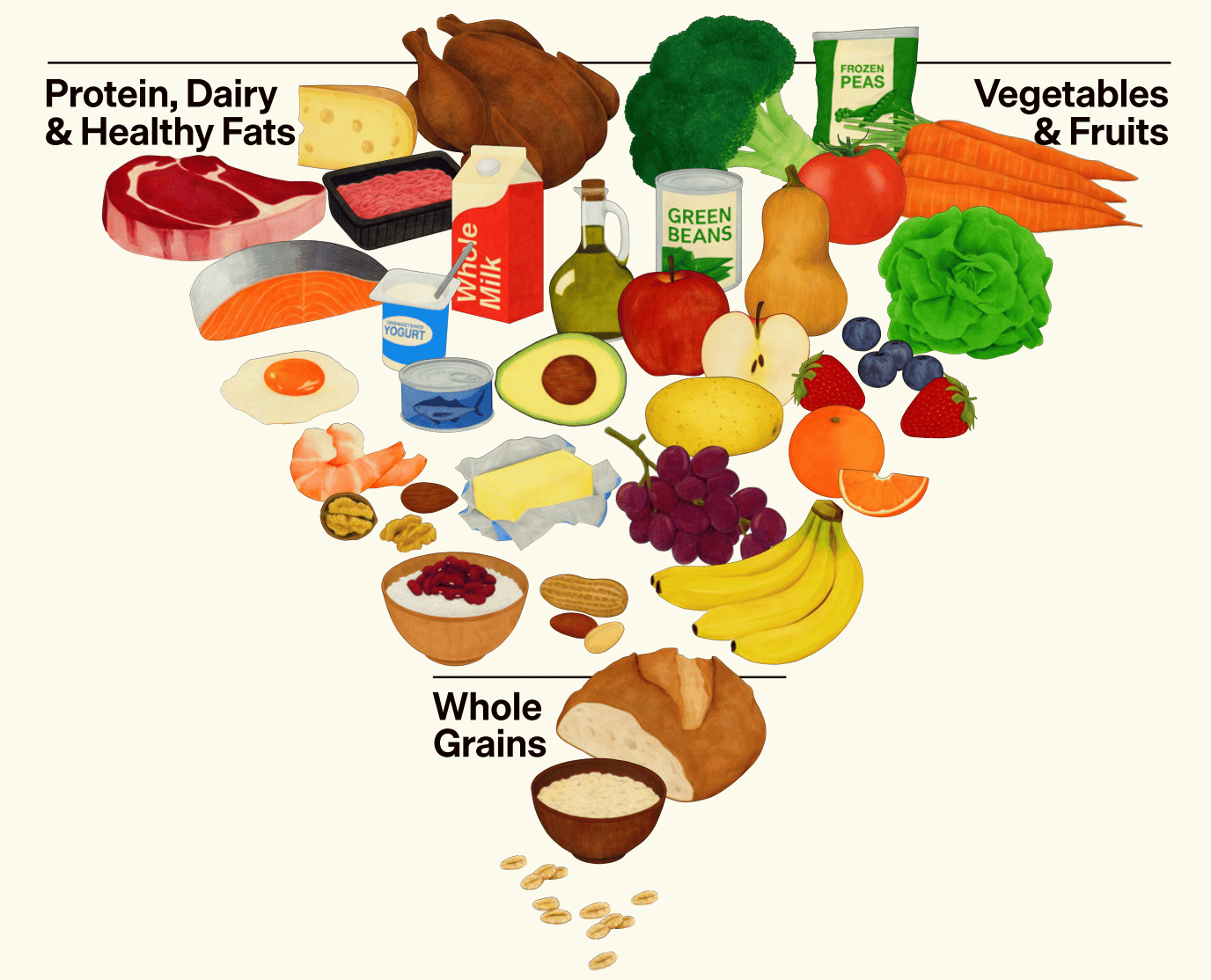

Depending on what you saw online, it may have sounded like everything we’ve been told about nutrition for decades was suddenly wrong or that we’re finally getting a long-overdue reset. Part of that feeling came from the introduction of a newly “flipped” food pyramid, shared with a lot of excitement and positioned as something entirely new.

That kind of messaging can feel unsettling, especially for parents who are already trying to make thoughtful food choices in a world that’s busy, expensive, and full of mixed messaging.

What stood out to me, though, wasn’t a dramatic shift in the advice itself. It was how different the conversation felt.

Because when you actually read the new dietary guidelines, much of the core guidance sounds familiar. The bigger change isn’t what they say, it’s how the guidance is being presented and talked about. And that matters, because visuals and messaging shape how information is understood, remembered, and shared.

This looks beyond the guidelines themselves to examine why the messaging feels so confusing, how mixed signals take hold, and why optics can overshadow context around food, health, and access.

The new guidelines aren’t all that unfamiliar

When you read the 2025–2030 Dietary Guidelines, much of the core guidance looks very familiar.

As an overview, the new guidelines continue to emphasize the same foundational principles that have been central to U.S. dietary guidance for years, including:

Eating an appropriate number of calories for age and developmental needs, with attention to portion sizes and overall energy balance

Prioritizing fruits and vegetables, with an emphasis on variety, color, and nutrient density

Choosing fiber-rich whole grains as a regular part of meals and snacks

Including a variety of protein sources, from both animal and plant foods, including beans, lentils, legumes, soy, nuts, seeds, poultry, seafood, eggs, and dairy

Limiting added sugars and sodium, particularly from packaged and highly processed foods

Keeping saturated fat below 10% of total daily calories, consistent with previous guidelines and broader nutrition consensus

From a pediatric perspective, the themes are also largely consistent with prior guidance. The guidelines continue to emphasize age-appropriate nutrition across childhood, including supporting growth and development, building healthy eating patterns early, and recognizing that children’s nutritional needs differ from adults, not just in quantity, but in context.

They also reinforce guidance around responsive feeding, appropriate beverage choices, and limiting added sugars during early childhood, areas that have long been emphasized in pediatric care.

That doesn’t mean everything is identical. There are updates and nuances, and the full guidelines are available for anyone who wants to read more.

But at the big-picture level, the substance of the advice itself has not been fundamentally rewritten.

This is where the disconnect starts to emerge. When the messaging suggests a sweeping reset, but the underlying guidance largely reflects continuity, it can leave people unsure what they’re actually meant to take away.

And for parents already navigating food decisions within real-world constraints, cost, time, access, and kids with very real preferences, that gap doesn’t feel clarifying. It feels confusing.

Why the messaging feels so extreme

A big part of the confusion around the new dietary guidelines isn’t just what was released, but how it was talked about.

In fact, the accompanying fact sheet described the update as “the most significant reset of federal nutrition policy in decades” and framed it as a correction after years of misguided advice.

Dietary guidelines are meant to summarize nutrition science and offer broad, population-level guidance. They help inform things like school meals, healthcare recommendations, and public education. They’re not designed to fix food access, affordability, or the many structural issues that shape how families actually eat day to day.

So this difference matters and is important to acknowledge.

Some of the language used to promote the new guidelines leans heavily on ideas of reset and personal responsibility. Phrases about “moving past decades of unhealthy eating” or “finding our footing again” can sound motivating, but they also quietly suggest that the problem has been confusion or poor choices, rather than the realities families are navigating every day.

When the rollout is framed as a sweeping reset or a correction for decades of “bad advice,” it puts a lot of weight on a document that was never meant to carry it. No set of guidelines can change food prices, create more time in the day, or undo an environment where highly processed foods are often the easiest and most affordable option.

When the messaging leans heavily into bold claims or dramatic visuals, it can make the guidance feel more disruptive than it actually is. Parents are left wondering whether something fundamental has changed, or whether they’re suddenly supposed to rethink everything they’ve been doing.

Instead of clarity, it creates uncertainty.

And that’s where the gap between the guidance itself and the way it’s presented starts to matter.

The return of the food pyramid

One reason the messaging landed so loudly is the return of a food pyramid visual.

The pyramid itself isn’t new. Versions of it have existed in the past, long before MyPlate became the standard visual used in schools, clinics, and federal nutrition programs. But this update introduced a newly flipped version, presented with a lot of excitement and framed as a clear break from what came before.

That framing matters, because visuals are powerful. Most people won’t read the full guidelines, but they will remember the image. And when a visual is positioned as revolutionary, it can signal a dramatic change even when the written guidance doesn’t fully support that interpretation.

This is where the disconnect starts to widen. The guidance itself remains largely familiar, but the visual suggests something much more disruptive. For many parents, that contrast is what fuels the sense that everything has suddenly shifted.

When the visuals and the guidance don’t fully match up

This is where things start to feel especially confusing for a lot of families.

In the written guidelines, the message around protein is pretty straightforward and familiar. They recommend including a mix of protein sources from both animal and plant foods. That includes things like beans, lentils, nuts, seeds, seafood, poultry, eggs, dairy, and yes, meat. This balance has been part of nutrition guidance for years.

But when you look at the flipped pyramid, that balance isn’t as easy to see.

Animal meat and fats are placed top and large, like a whole chicken, while plant-based protein sources are much harder to spot. For someone glancing at the image, the takeaway can easily become, “I should be eating a lot more meat,” even though that’s not what the written guidance actually says.

You may also hear this shift described as “ending a war on protein.” But protein has long been part of dietary guidance. The bigger change here is how strongly animal protein is being highlighted visually, which can make the update feel more dramatic than the guidance itself. Very typical of the MAHA movement to create a problem that never existed–AKA “A WAR ON PROTEIN” and then seem like the knight-in-shining-armor saving the day. The reality is that protein was never missing from the conversation.

If we want to talk about what’s actually missing from many diets, for both kids and adults, fiber is a big one.

Most Americans, including children, don’t get nearly enough fiber. Fiber supports digestion, helps regulate blood sugar, and plays a big role in gut health. For many kids, it’s also an important part of preventing or managing constipation.

Fiber comes from a variety of foods, including:

Whole grains like oatmeal, whole wheat bread or pasta, bran cereals, granola, chia seeds, and whole-grain waffles

Fruits like pears, raspberries, apples, prunes, oranges, kiwis, strawberries, and blackberries

Vegetables like carrots, broccoli, leafy greens, avocado, Brussels sprouts, squash, and spinach

Legumes like beans, lentils, chickpeas, and green peas

If you want help putting all of this together in a realistic way, PedsDocTalk’s Toddler Nutrition Guide walks through fiber, protein, iron, vitamins, and more, with meal planning guidance that fits real family life.

The same thing happens with fat. The guidelines still recommend keeping saturated fat under 10% of total daily calories, just like previous versions. But when animal fats are visually emphasized, that recommendation becomes harder to connect. If you’re being shown an image that highlights animal fats, it’s not clear how that fits with the idea of limiting saturated fat. The two messages don’t sit neatly together.

Most parents aren’t reading every paragraph of the guidelines. They’re absorbing what stands out. And images tend to stand out far more than text.

So when the picture and the words aren’t clearly aligned, people are left to fill in the blanks. That’s often where confusion starts.

And that’s the hard part, because clarity is exactly what dietary guidelines are meant to provide. Their role is to offer clear, consistent guidance that people can understand and use. When the messaging muddies that clarity, even unintentionally, it makes food decisions feel harder than they need to be.

The bigger issue the guidelines can’t directly solve

Once you separate the guidance itself from the messaging around it, a bigger issue comes into focus.

Dietary guidelines do play an important role. They help inform large systems like school meals, federal nutrition programs, healthcare guidance, and public health education. In that way, they absolutely matter.

But they’re still guidance.

They don’t control food prices. They don’t increase household budgets, create more time in the day, or change what’s stocked on store shelves. And they don’t undo the broader conditions families are making food decisions within.

Those decisions are shaped by very real constraints.

Cost matters. Fresh, minimally processed foods are often more expensive.

Access matters. What’s available can look very different depending on where a family lives, shops, or sends their kids to school.

Time matters. Many parents are juggling long work hours, childcare, and exhaustion.

Marketing matters. Highly processed foods are aggressively promoted and widely available, especially to children.

These forces have shaped how Americans eat for decades. And they help explain an important reality: no version of the dietary guidelines, past or present, has ever been widely followed at a population level.

That isn’t because the guidance was unclear or misguided. It’s because guidance exists inside systems. It doesn’t override them.

So when the story being told suggests that past advice is the reason families struggle with food choices, it misses the mark. It shifts attention away from the conditions families are navigating every day and places responsibility where it doesn’t belong.

You see this framing in the fact sheet, which goes as far as suggesting that decades of poor health outcomes stem from previous government recommendations that “incentivized low quality, highly processed foods,” positioning guidance itself as the primary driver of today’s chronic disease burden.

Which is why moments like this are less about rewriting guidance, and more about how we support families as they make food decisions in real life.

What I want parents to know

When something like the dietary guidelines gets rolled out with a lot of hype, it’s easy for parents to pause and wonder, Am I supposed to be doing something differently now?

That question makes sense.

But here’s the thing. Even in clinical care, guidelines are exactly that: guidelines. They help inform decisions, but they’re never the whole story. As providers, we’re always layering them with context: a child’s age, growth, medical history, family circumstances, access, and what’s actually realistic.

Parenting works the same way.

Guidance can be helpful, but it’s just one piece. It doesn’t replace everything else you’re already considering when you feed your kids. It doesn’t override your routines, your budget, your time, or your child’s preferences. And it certainly doesn’t mean you need to rethink everything because a new graphic showed up online.

What parents tend to need most in moments like this is reassurance.

Reassurance that the basics haven’t suddenly changed.

Reassurance that feeding kids is about patterns over time, not reacting to every new headline.

Reassurance that doing “pretty good, most of the time” actually goes a long way.

Zooming out helps. No single meal defines a child’s health. No single food choice outweighs the bigger picture of how a family eats over weeks and months. Progress comes from consistency, flexibility, and making choices that work for your family, not from chasing perfection.

Guidelines can inform the conversation. They shouldn’t create stress around it.

Why this matters

What makes this moment feel important isn’t the release of a new graphic or even a new set of guidelines. It’s the level of attention people are paying.

There’s real interest right now in food, health, and chronic disease. Parents are asking questions. They’re trying to make sense of conflicting messages. They want better for their families. That matters, and it’s worth honoring.

That’s also why the framing matters so much.

When the focus stays on visuals, resets, or dramatic shifts in tone, it risks missing a bigger opportunity. The opportunity isn’t to convince families they’ve been doing everything wrong. It’s to support them in a system that often makes healthy choices harder than they need to be.

Real progress doesn’t come from flipping a pyramid. It comes from how this kind of attention is used, to improve access to nutritious foods, to support families through policy and programs, and to make it easier for evidence-based guidance to fit into real life. It comes from consistency, trust, and meeting families where they are.

Dietary guidelines can help inform that work, especially in places like schools, healthcare, and public programs. But they work best when they’re part of a broader effort, not when they’re positioned as the reason we got here in the first place.

If this moment leads to more thoughtful conversations, better support for families, and more focus on the systems that shape how people eat, then that attention is well spent.

If you enjoyed this newsletter, I’d love for you to share it with others! Screenshot, share, and tag me @pedsdoctalk so more parents can join the community and get in on the amazing conversations we're having here. Thank you for helping spread the word!

On The Podcast

In this solo episode, I am opening up about a big life change. I recently resigned from my clinical job. On paper it may sound simple, but the story under it holds a lot of layers, emotion, and growth.

I talk about what led to my decision, what it brought up from my childhood, and how this shift is changing the way I raise my kids. If you grew up chasing safety, grades, or approval, parts of this will feel familiar.

In this Follow-Up episode, Dr. Mona revisits one of the most downloaded PedsDocTalk conversations, her discussion with Dr. Loretta Breuning on how rewards and threats shape a child’s brain.

They break down why yelling, pleading, and bribing often backfire, and how attention itself can accidentally reinforce behaviors parents want to stop. You will hear why giving in after resistance makes behaviors stronger over time, and how inconsistency trains kids to escalate.

This episode focuses on building healthier reward pathways with clarity and consistency, without fear, shame, or constant power struggles. If certain parenting moments feel stuck on repeat, this conversation helps explain why and what to do differently.

On YouTube

Newborns often struggle with crib or bassinet sleep because their brains and bodies are wired for warmth, movement, and contact, and their sleep cycles are short and light. You can make transfers easier by watching for deep sleep, using calm and slow movements, supporting their nervous system with touch and sound, and keeping wake windows in a healthy range. This is a learned skill that takes practice, and a mix of safe independent sleep and contact sleep is common and completely okay.

Ask Dr. Mona

An opportunity for YOU to ask Dr. Mona your parenting questions!

Dr. Mona will answer these questions in a future Sunday Morning Q&A email. Chances are if you have a parenting concern or question, another parent can relate. So let's figure this out together!

Reply